Our Findings

Divided Landscapes

The BMP used a unique, mixed methods approach to describing and explaining patterns of activity space segregation in the historically divided city of Belfast, including (1) GPS tracking allied with GIS methods of data capture, analysis and representation; (2) walking interviews, and (3) a large scale questionnaire survey. In this section, some of our key findings are summarised under the headings Divided Landscapes, Narrated Landscapes and Shared Landscapes.

Most research on urban segregation has focused on global patterns of residential division captured at a single moment in time, often using government census data about where people live in cities. The Belfast Mobility Project examined how segregation may arise through the patterning of everyday movements and use of activity spaces beyond the home and over time. Based on analysis of over 20 million GPS tracking data points, the GIS image presented opposite visualises how members of Catholic and Protestant communities in North Belfast tend to use different pathways and frequent different kinds of activity spaces. Indeed, as Figure 1 below illustrates, residents spend most of their time in spaces located in their own communities and little time in ‘outgroup’ areas.

Percentage of time spent within or moving through different types of spaces

GPS Tracks of 196 participants by commmunity affiliation. Click to View Map Full Screen

Examples of T-Communities in North Belfast

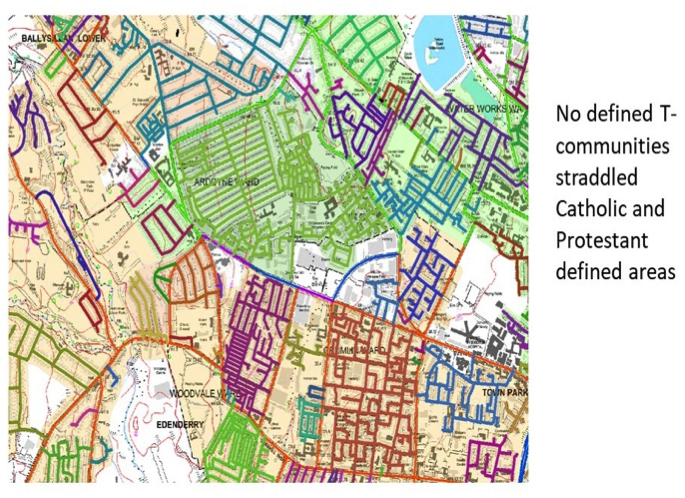

Two further aspects of the patterning of activity-space segregation in North Belfast are worth noting. Firstly, to a large extent, it is maintained by residents’ movements through, and use of, tertiary street networks or ‘T-Communities’ (Grannis, 1998). Such networks form systems of social and spatial (dis)connection between neighbours, enabling segregation to emerge even in contexts where different communities live in close proximity to one another. Grannis (1998) has labelled such networks ‘T-communities’.

Second, activity-space segregation marked social relations even in ‘public’ spaces that would ordinarily be sites of urban mixing. For example, parks are typically conceived as quintessentially open and inclusive facilities designed for members of all communities to enjoy freely. However, our walking interview data suggests that the use of parks in North Belfast is often organised along sectarian lines, with residents using different access points and sometimes avoiding completely areas associated with the ‘other’ community. At this point in North Belfast’s history, we would describe areas such as parks as ‘liminal spaces’ – they are simultaneously public, open spaces and sectarian and divided spaces. In their everyday lives, local residents must negotiate this ‘in betweenness’ as they engage in such ordinary activities as walking their dogs or taking their kids to the play areas.

A 3.5-metre high peace wall was erected in 1994 to divide Alexandra Park – a Victorian park located in North Belfast – into Protestant and Catholic areas; however, in 2011, the photographed gate linking the two communities was installed, signifying an opening up of the space.

The Gate in the Alexandra Park Peace Wall

Narrated Landscapes

Curb stones painted red, white and blue, a common marker of Protestant areas.

Thirty-three residents of North Belfast participated in walking interviews as part of the Belfast Mobility Project. During these walks, which usually lasted between 45 minutes and two hours, participants were asked to imagine they were tour guides, taking the researchers on a typical journey through their local area to discuss the impact of community divisions and the associated symbolic landscape on their perception and use of space.

Here, two tracked walks demonstrate markedly different patterns of movement between a Catholic participant from Ardoyne and a Protestant participant from the adjacent Glenbryn neighborhood. Their respective perceptions of threat, shared space and communal identity differ in ways that help to sustain activity-space segregation. Click on the maps below to hear the participants’ commentary about how features in the landscape and broader social dynamics impact their mobility choices.

Participant A

Click the button on the map below to watch an animation of the walking interview, including audio and photographs from key stops along the way.

Participant B

Click the button on the map below to watch an animation of the walking interview, including audio and photographs from key stops along the way.